History of Alexander the Great - part 2

- Published in History

Alexander III of Macedon, commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a King of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon

Alexander III of Macedon, commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a King of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon

Part 2 - Life and history of Alexander the Great. The unstoppable and unbeatable Greek leader Alexander is conquering one by one the territories of the vast Persian empire on his way to India... The battles, the tactics, the genius strategics...

Part 2

In the Footsteps of Gods

Egypt had been conquered by Persia several times and had always managed to throw off the yoke. This last time, however, Persia had made it stick. Egypt was conquered and didn't like it one bit.

They were eager to throw off their masters and saw their opportunity when Alexander came calling. Rather than put up a fight, they lay down their weapons and opened their arms, proclaiming Alexander to be the son of Re (the sun god). In one of the strange instances that make for wonderful historical asides, Alexander traveled by himself through the desert to visit a temple to Re, going days without food or water before finally finding what he was looking for. As only he could, he returned and proclaimed that he had been visited by Re himself and that the god had anointed Alexander the new ruler of Egypt. The Egyptians, believing in signs and seeing a way out of the Persian predicament, agreed.

Map of the Alexander's route to Egypt

The result of all this was that Alexander was proclaimed ruler of Egypt. To commemorate the Egyptian people's faith in him, Alexander designed and had built a city, named after himself, naturally. This was the fabled Alexandria (one of many such-named cities), which would become one of the most famous cities in the world.

Two years later, Darius desperately wanted to avoid the mistakes that led to his defeat at Issus. He was still the emperor of the Persian Empire, and he still commanded an army of many thousands. (Some historians, notably Arrian, claim that the Persian army numbered 1 million at this battle.) He could still also choose the field of battle. At Gaugamela, he chose a wide open plain, in which he could deploy his entire army to its best effect.

By this time, Alexander was flush with victory again, having rolled up much of the western part of what used to be the empire. He still hadn't lost a battle and was considered a military genius who would take any advantage in order to win the day. He had still inferior numbers, but that hadn't stopped him from winning before. One of Alexander's commanders, a man named Parmenion, advised Alexander to attack at night and gain the element of surprise. Alexander decided against it, but Darius feared that sort of attack all to well and kept his men standing on the battlefield all night. Fearing the worst, Darius created the worst. Alexander and his men, on the other hand, had a good night's sleep.

The battle unfolded in much the same way as the Battle of Issus, with the Persians taking early advantage and then Alexander's cavalry delivering a knockout blow near the end. The deciding factor again was Alexander's ability to see what was happening during the fighting and shift resources were they were needed most or could take full advantage. In an era of communication by messenger and long before aerial reconnaissance, this ability of Alexander's was a prime factor in his being able to win when winning seemed out of the question. Alexander's victory at Gaugamela, however, viewed from Darius's point of view, must have been all the more puzzling, especially since the emperor was sporting some surprise new weapons this time around: some war elephants imported from India and 200 fully armed war chariots. The Macedonian army made quick work of it all, though, and drove their point home. Darius, again, was sent packing, far to the east.

Taking Over a Huge Empire

Meanwhile, Alexander marched south, to Babylon. This ancient capital was a fabled city, home to the Hanging Gardens and the throne of Nebuchadnezzar and all manner of other rulers. Babylon, the gateway to the Persian Gulf, was known to be a heavily fortified city. The residents had withstood sieges during the rules of Cyrus the Great and Darius I. Alexander assumed the worst and readied his men for a long struggle, possibly on par with the one needed to subdue Tyre. But when the Macedonians reached the ancient capital, they found the gates to the city thrown wide open and the welcome mat rolled out. Whether the Babylonians were ready for a new leader or they knew that they couldn't withstand an attack by the formidable invaders, Alexander didn't care. He was received as a hero and treated like a god.

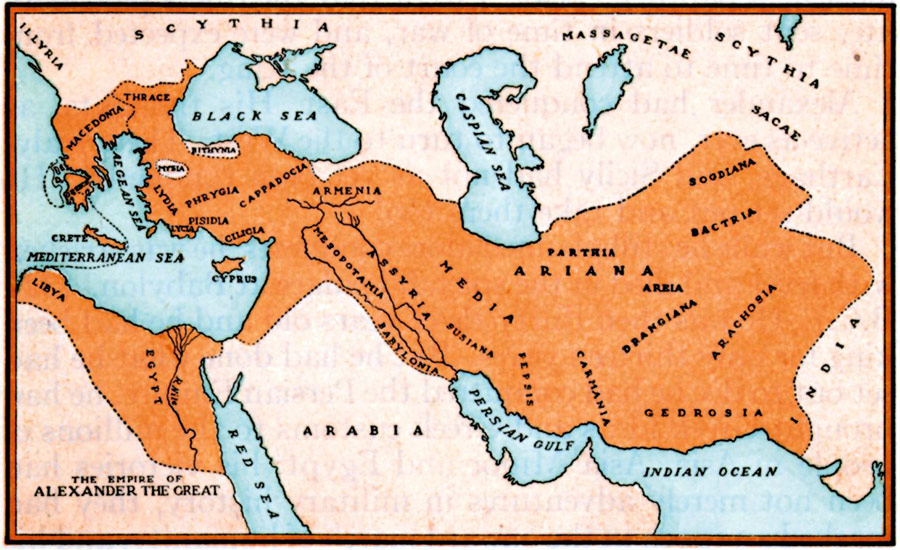

Map of the Alexander the Great empire

As he had done throughout his conquests, Alexander left the local government in place, swearing the leaders to loyalty to him and him alone. He sat on the throne of the Great King and attended to the people's wishes for a time. In this, he saw the big picture: He would need more than soldiers to capture the hearts and minds of the Persian people. It was then that his vision to grow grand, if it wasn't that big already. It was in Babylon that Alexander began to really see himself as the bridger between two worlds, as the leader of a new Greco-Persian civilization that would incorporate the best of the both and eliminate the worst of each. He took a great interest in the Persian religions and listened patiently to its priests.

His men, however, had other ideas. They grew impatient, both with Alexander's attention to eastern ideals and to what they saw as his dallying in a foreign capital. They wanted to keep moving: If they weren't headed home, then they wanted more conquests. To that, Alexander agreed.

The Macedonian army, its numbers swelled by Persian recruits, then marched to another of the great Persian cities, Susa. Again, the outcome was the same, although the people there were not as welcoming as the Babylonians had been. Still, Alexander gave his men large shares of the spoils before sending it back to Macedon.

Onward they went, moving ever deeper into the heart of the Persian Empire. Alexander's stubbornness required that his men march through a blinding snowstorm, but they did it readily enough. The next target was Persepolis, which was in technicality the chief city of the empire. Babylon was the fabled ancient capital, yes; but Persepolis was the real seat of power, the home of the palace of the Persian kings. If Alexander showed reverence for Babylon, what would he do in Persepolis? Some of his men worried that they would be stuck again in some faraway city; many missed their families and their home life terribly. But they were devoted to Alexander. They reveled in the riches that they found, riches beyond imagining. They reveled in the celebration of the sacking of yet another Persian city. But they were understandably shocked when Alexander set fire to the royal palace itself.

The darius family to Alexander

Alexander thought of himself as both the successor to Darius and as the bringer of new light and new civilization. He no doubt thought that the royal palace was a thing of the past, a bridge to older times, before his arrival on the scene. But historians have a difficult time explaining why he would destroy what at that time was one of the world's most beautiful buildings, full of the world's most beautiful things. Some sources say that he was drunk (both with wine and power) and didn't know what he was doing. Other sources say that it was a symbolic act, as if he, the new king, would arise from the ashes of the old. Whatever the reason or the circumstances, burn the royal palace Alexander did. Thousands of years of history and art went up in flames.

Proclamation of a New God

Also during this time, Alexander began to demand that his subjects treat him as a god. He thought of himself as their deliverer, as their savior from the cruelty of Darius and the Persian emperors and kings before him. He also thought of himself as more than just a man. In his own mind, he was invincible, a genius on the battlefield and in political matters. He foresaw a time when he would be the master of the known world. His thoughts full of such grandeur, he styled himself a god and demanded obedience from his new people.

Gold coin of the Alexander the Great

Alexander and his men stayed through the winter before moving on, leaving local leaders in charge of Persepolis, with the promise that Alexander would be back to accept the throne of the empire. Then, he and his men went in search of Darius (who was, technically, still the emperor). By this time, Darius had become convinced that he couldn't defeat Alexander and had reduced himself to fleeing the countryside. His military commanders, none too pleased with this change of events, seized control of the situation and eventually seized control of Darius himself. His own viceroy, Bessus, took charge of Darius and kept him as a prisoner. The main Persian army was camped to the north, near the Caspian Sea. Alexander followed, of course.

When the two armies were within in sight of each other, the result didn't change. Bessus, not at all sure that he wanted to fight, led his men in a further retreat, further north, fading into the countryside. They left Darius behind, dead of stab wounds. When Alexander discovered the dead emperor, he had him sent back to Persepolis and buried with full royal honors. The quarry, however, was still to the north.

Alexander led his men across the region of Bactria and into the fabled mountains known as Paropanisus. (We call this the Hindu Kush today.) Along the way, some of Alexander's men, thinking that they would never see their homes again and convinced that their leader was going mad, began to plot against him. A great many of the men were still loyal to Alexander, however, and the plot was soon discovered. It was in a place called Drangiana that the first hints of Alexander's madness surfaced.

Philotas, the son of Parmenio, one of Alexander's most trusted and successful commanders, was suspected of being involved in the plot against Alexander. Philotas and his father were two of the king's dearest friends and had served with him from the beginning. However, Alexander must survive and teach a lesson to anyone wishing to oppose him. In a fit of calculated rage, Alexander ordered Philotas executed. Not content with that, however, he also ordered Parmenio killed, figuring that his loyalty would be in question from that point forward.

Alexander and his men caught up with Bessus, the runaway rebel, eventually. The result wasn't much of a battle, since the Persian forces were thinned from defeats and exhaustion. Bessus was captured and then cruelly tortured before being killed.

Alexander was master of the Persian Empire, but was he master of himself? He had become increasingly erratic and impulsive, even moreso than he had ever had been. These qualities had served him well on the battlefield, where he could use his "sixth sense" to discover where to penetrate the enemy's defenses; but the same qualities weren't working so well in the administration of an occupied territory. When Parmenio's cavalry refused to follow the army east, Alexander ordered them to go home (which is probably what they were ready for at that point anyway).

Impatient and still seeking some elusive goal, Alexander ordered his men to march ever eastward, in search of they knew not what. If Alexander had a goal in mind, he didn't readily share it with his troops. Eastward and northward hey moved, defeating armies as they went, over hundreds of miles of unfamiliar terrain, past the ancient trading post of Samarkand, and on into the heart of Asia.

Of Friends and Enemies

It was in 328 B.C. that Alexander made perhaps his greatest mistake. It wasn't even on the battlefield. He and his men had conquered the large areas of Bactria and Sogdiana, in the north, and Alexander had rewarded his old friend Cleitus by placing him in charge of the entire area. Cleitus it was who had saved Alexander's life many years before, at the Battle of Granicus, leading a fierce charge to relieve the king, who suddenly found himself surrounded by the enemy with no way out. Cleitus it was who had stood by him through all the battles and all the conquests and all the "questionable" behavior. But Cleitus it was one night who not only defended Parmenio, Alexander's trusted friend whom the king now considered a traitor who got what he deserved, but also criticized the king himself for thinking himself a god and adopting the ways of the Persian people. Alexander wouldn't dare to hear this kind of talk, not even from one of his closest and oldest friends, and killed Cleitus himself.

Alexander's triumphal entry in Babylon

If Alexander were willing to kill his best friends, what would he do to deserters or those who plotted against him? Fear of Alexander's wrath is how historians describe the Macedonians' motivation for continuing to follow Alexander from this point on. No doubt, many believed that he was a god, having seen his almost superhuman ability to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat and to survive battle wounds that would have killed "normal" men. No doubt, many believed him when he said that he was a god, the deliverer of light into the world of darkness. No doubt, they preferred to march with him than struggle against him.

So on they went, ever eastward, in search of the edge of the world. The days and weeks and months passed by. In 327, one year after the death of Cleitus, Alexander and his men claimed the final piece of the Persian puzzle, defeating the Sogdian warlord Oxyartes. At last, all of the Persian Empire was Alexander's, literally.

The spoils of that victory included the warlord's daughter, Roxane. She became Alexander's wife and queen. It was more a political marriage than anything else, but it was a marriage all the same, with all the royal trappings that that entailed.

Still, Alexander looked eastward, toward India, the edge of the known world. Many of his men were tired and homesick and didn't want to follow him any further. They were suspicious of his motives and wanted desperately to return to a life that they knew and understood, that carried less threat of death every day on the field of battle. But march on with him they did, concluding that perhaps they would reach the end of the road soon and head back toward home. The army at this time was also swelled by new recruits, Persian soldiers serving alongside the Macedonians that they had once fought. This was Alexander's vision come true: east and west fighting side by side.

To the Edge of the World

The multinational force crossed the high and dangerous Hindu Kush mountains (through the notorious Khyber Pass) and entered India. They crossed the Indus River in 326 and marched into the territory claimed by the Indian King Porus, who ruled a vast domain that included much of what is today Pakistan.

Porus had perhaps heard of Alexander, the king from the west who won great victories against long odds. Porus, however, was confident in his own troops, especially his secret weapon—200 war elephants. Alexander is thought to have had slightly more troops than Porus, 36,000 to 30,000; but the war elephants were a wildcard that the Indian leader hoped to play to its fullest.

Alexander the Great conquering India

The battle took place along the Hydaspes River. The war elephants were lined up along the river, preventing Alexander and his men from crossing. For about two weeks, the Macedonians marched up and down the riverbank, not attacking but appearing to be ready to attack. The Indians followed suit, expecting an attack at any moment. None came.

One night, Alexander ordered his men to cross the river in secret. The war elephants were nowhere to be found at the point of crossing, and so over the Macedonians went. Was Porus lulled into a false sense of security? Did he make a mistake? Did Alexander get lucky? Whatever the reason, a large force of Macedonians made it over the river and into the midst of the Indian troops before they knew what hit them. The rest of the army crossed, and the battle was on.

Alexander himself led a charge of a small group of men right at the elephants. It was Gaugamela all over again, as Porus withdrew troops from the center of his lines to support the elephants on the flank. Then, when the center was weak, Alexander's phalanx swept in for the kill. The result was mass confusion on the Indian side, with infantry, cavalry and war elephants all mixed together, impeding one another's progress. The advantage that Porus had hoped to gain with his war elephants turned against him when the great beasts stampeded, trampling friend and foe alike in their rush to escape the carnage on the battlefield. In the end, many lay dead on both sides. Alexander was the victor, but the cost was high. He lost many men and even his most trusted horse, Bucephalus, who had served under him since the beginning.

Still, they marched on. The men finally would go no further, none of them, when they reached the Beas River. They were thousands of miles from their home and hundreds of miles away from anything that might resemble friendly territory. Alexander, overcome with grief at the loss of his beloved horse and so many men, agreed that it was time to go home.

Turnabout Home

The great journey back to Persia took three phases. One group of soldiers sailed on ships through the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf to Babylon. One group marched across the region of Hyrcania, south of the Caspian Sea. Alexander led the third group across the rocky Gedrosia Desert and to a predetermined meeting point with the army landbound army. Both armies entered Susa together.

What they found on their return—and this was the same in Babylon, where Alexander made his new home—was disorganization and corruption. Left to their own devices and without a strong hand to keep them in check, the local leaders that Alexander had sworn to loyalty went about their own business and tried to take little pieces of the new empire for themselves.

Alexander returned and reinstituted his iron grip. But he also realized that he still needed to show a good deal of tolerance for the native people and their beliefs. To strengthen his hold on the situation, he got married—again, this time to two women. One was Statira, daughter of Darius; the other was Parysatis, daughter of Artaxerxes III, another Persian ruler. In the same wedding ceremony, 80 Macedonians married 80 Persian women. The union was complete, in Alexander's mind.

But he couldn't keep his mind from the belief that he was above it all. Still undefeated on the battlefield and now back in charge of a huge empire that he had slaved eight years to conquer, he went about making himself the center of attention in all facets of Persian life. He still dressed like a god and demanded that his subjects (even, still, his own troops) refer to him as such. He ordered built temples where the people would worship him. He demanded that the cities in faraway Greece build temples to him. When the men who had followed him to the edge of the earth and back quarreled, he sent them home (again, which is what they probably wanted anyway, and they were undoubtedly glad that he didn't have them killed).

At the Last

The men who did stay behind grew increasingly disappointed in Alexander, who seemed to place more trust in the Persian soldiers and leaders than he did in the men who fought alongside him to conquer the very men that he was having more faith in now. Alexander grew increasingly convinced that he was above it all.

In 324 B.C., Alexander's closest companion, Hephaeston, died. After this, the great warrior king lost the will to live. He had nothing of his old life except the memories. His friends and companions were gone. He was living the life of a foreign ruler in a foreign land. His men were either back home or distrustful of him. He took to drinking large amounts of wine to drown his sorrows.

In June 323, he became ill. Whether he caught a fever or as poisoned, no one can say with any certainty. What is known is that he died, on June 13.

After his death, his empire crumbled. It was originally split up into three parts, with supposedly strong leaders at the head, in Egypt, in Syria, and in Pergamum. (Click here for map of the empire divided.) But no one but Alexander—with his unique combination of genius, fear, wrath, and determination—could control something so big. Within a few years, the empire was wracked by civil war. But although the fighting continued, the learning, culture exchange, and opening of world views did not. Alexander brought the world closer together in a way not seen before or since.

Source:Social Studies for Kids

Video: The battle of Gavgamela, Alexander deceiving Darius