The Persian Invasion in Greece: Marathon

- Published in History

Battle of Marathon: On August. 12, 490 B.C., an outnumbered Athenian army defeated the Persians, repelling the Persian invasion

Battle of Marathon: On August. 12, 490 B.C., an outnumbered Athenian army defeated the Persians, repelling the Persian invasion

The Battle of Marathon took place in September 12th, 490 BCE*, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian Imperial force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes.

It was the culmination of the first attempt by the Achaemenids' Persian Empire, under King Darius the Great, to subjugate Greece city states. The first Persian invasion was a response to Greek involvement in the Ionian Revolt against the Persian domination, when Athens and Eretria had sent a force to support the cities of Ionia in their attempt to overthrow Persian rule. The Athenians and Eretrians had succeeded in capturing and burning the Persian city of Sardis, but were then forced to retreat with heavy losses. In response to this raid, Darius the Great swore to burn down Athens and Eretria. At the time of the battle, Sparta and Athens were the two largest city states.

After Darius the Great's fleet was destroyed in 492 BCE, he sent envoys to the Greek states in Spring 491 BCE, demanding that each city-state send him the earth and water of vassalage.

This was accepted by many of the states, from the northern Aegean to the Dardanelles, but this was refused by Athens and Sparta. With so many of the city-states submitting to him, Darius felt Greece was ready to fall to him.

The Persian army broke in panic towards their ships, and large numbers were slaughtered

In the spring of 490 BCE, Darius assembled a fleet of over 600 ships and a large army near Tarsus. This armed force was jointly commanded by Darius' nephew Artaphernes and a Median nobleman named Datis. They had with them also an exiled Athenian named Hippias as a guide and advisor.

The fleet traveled through the Cyclades to Naxos, which they then assaulted and looted. The Persian fleet, having secured command of the Cyclades and the Aegean Sea, moved forward with the invasion. The fleet sailed from island to island, conscripting troops and taking hostages. The Imperial army met with only slight resistance at Carystus, the southernmost town of Euboea. The Iranians then laid siege to Eretria, and after a week of resistance, the city finally fell to a betrayal from inside the city. After the pillaging the city, they moved on to the shores of Attica.

Hippias had advised the Imperial army commanders that the Bay of Marathon was the most logical place for landing and disembarking the army. It had a sheltered bay, a long, firm, flat plain between the mountains and the sea, and was protected from the north and east winds. It was also within an easy march of Athens, which was only thirty-eight kilometers away. The long and sandy beach could accommodate all of the Persians' 600+ ships. Also, the open plain of Marathon was perfect for the use of the Persian cavalry, against which it was thought the Athenian infantry would be ineffective.

The Persians situated their camp near the Makaria Spring, which provided a plentiful supply of water, and the nearby plain had good grazing for the horses.

Hippias' information on Athens would prove to be out of date, as the government had had many changes since his exile. The power now was in an elected Commander in Chief, called a Polemarch, and new military officers called Strategoi, and the new government was determined to maintain Athens' independence. The Commander in Chief was Callimachus. The main planner and strategist was Miltiades, who also served as a commander of one of the ten main infantry divisions (Lochoi).

The Athenians were warned of the Persian invasion by a series of beacon fires. They sent word to Sparta by fast runner, and the Spartans announced that although they were sympathetic to the Athenian cause, they were forbade by religious belief to send their troops into combat until after the full moon. The full moon would not be for another six or seven days, as it was only the 5th of August. This meant for most of a week the Athenians could not count on any support from Sparta. The Athenians did manage to get a small contingent of troops (about 600 Hoplites) from Plataea.

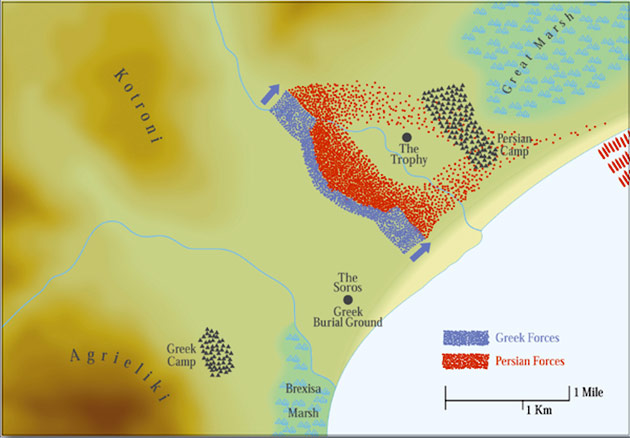

The first instructions for battle from Miltiades were to contain the invading army and block its march on Athens. A force consisting of approximately 9000 Athenians and 600 Plataeans took up their position at the southern end of the Plain of Marathon with Mount Agrieliki on their left flank, the sea on their right flank, and the Brexisa Marsh to their rear. They had effectively blocked the road to Athens. The Athenian commanders had trees cut down and manhandled into position with their branches facing the Persian line to create a defense against the Persian cavalry.

For the next few days, till the 11th of August, the lines remained static, five kilometers apart, neither side willing to make a move to attack the other. The Athenians did not wish to advance onto the plain where the advantage would lay with the Persian cavalry and archers.

The Persians on their part remained stationary, as they did not want to engage the Greek line where it had taken up a position that was unfavorable to the Persian cavalry. The Persians were also hoping for a betrayal in Athens itself by the friends of Hippias.

General Datis, after becoming frustrated by the stalemate, put his own battle plan into action. During the night on the 11th-12th of August, he reboarded his ships with most of the cavalry as well as the infantry under his command, and, slipping away under cover of darkness, sailed for Phaleron Bay, leaving Artaphernes with a holding force facing the Athenians. Miltiades' scouts discovered the departure and quickly informed him of it. The Athenian leaders were summoned, and Miltiades' laid out the only possible chance of a Greek victory. As it would take the Persians a minimum of ten hours to reach Phaleron by sea, and disembarkation would take a few more hours, by which time it would be late afternoon or early evening. This gave the Athenians one chance for victory. They must defeat the remaining Persians and return to Athens before Datis arrived.

Video: The battle of Marathon

The Persian general, Artaphernes, was now without most of the cavalry, and a large portion of the infantry, but he still retained a large number of archers. With this in mind, Miltiades set forth a plan for attempting to quickly defeat Artaphernes' force so that the Athenians would be able to return to Athens to meet Datis' force. At 5:30 am, with time short, and only three hours in which to win the battle, the order to attack was given.

The Athenian army was drawn up in a battle order as planned by Miltiades. Callimachus commanded the right flank, the left flank was held by the Plataeans, and the center was commanded by Themistocles and Aristeides. The Athenian tactic was to use a long, thin center with the ranks reduced to four instead of the usual eight, with deep formations deployed on the two flanks. The main strength would be in the massed formations on the two flanks, which were to drive off the Persian flanks and then wheel and attack the Persian center.

The distance between the two armies was approximately fifteen hundred meters when the advance was sounded and the Athenian ranks moved forward at 6:00 am. The advance started at a brisk walk, then developed into a trot, and then into double-time as they rushed the last 140-150 meters. This fast advance was the first double-time advance by Hoplites according to Herodotus, and was done in hope of avoiding the worst of the hail of arrows from the Persian troops. In the center, the Persian royal troops, made up of the Immortals and other elite units, began forcing the Athenian center back. Meanwhile, on either flank the Athenians' deep formations had crushed and carried before them the Persian flanks, putting them to flight.

With the Persian flanks destroyed or put to flight, the Athenian and Plataean flanking forces wheeled inward, hinging upon the retreating Athenian center, catching the Persian elite troops in a perfect pincer maneuver. The Persians had no choice but to try to fight their way back to their ships. Many of the Persians drowned in the marshes where they had retreated to. Others who tried to flee into the sea were also drowned. By 9:00 am, the beaten up Persian surviving royal troops and such ships that could get away were heading out to sea and toward Phaleron. The Persians had lost 6,400 troops, and an uncounted number of prisoners and wounded, along with seven ships. The Athenians had lost only 192 dead, including their Command in Chief, Callimachus. Miltiades detached one division under Aristeides to guard the prisoners and captured equipment, and quick-marched his troops back to Athens.

When the Persian invasion force arrived, they found the Athenian army had already taken up defensive positions at Cynosarges, south of the city. Datis found Athens to be well defended, and attempts to land would have been useless, so he anchored and waited for Artaphernes to arrive. When Artaphernes arrived with his battered and depleted, force, there was only one course of action left for the Persian fleet, and that was to return to Asia.

In 489 BCE, Miltiades made an unsuccessful attempt to regain control of the Aegean islands that had capitulated to the Persians, but he did not have sufficient naval force to accomplish this task. After failing in his blockade of Paros, Miltiades was imprisoned at Athens for his defeat, and he died soon afterward of a wound received at Paros. Thus was the victor of Marathon rewarded.

* Philipp August Böckh in 1855 concluded that the battle took place on September 12, 490 BCE in the Julian calendar, and this is the conventionally accepted date. However, the Spartan calendar was one month ahead of that of Athenians, which places the battle on August 12th, 490 BCE.

The verdict of Marathon proved that far from being rudimentary, the introduction of a true heavy-infantry militia and shock battle was, in fact, a brilliant and a revolutionary idea.

Marathon plain

Map of the battle:

The Battle of Marathon was entirely an antithesis of military and political traditions. Cavalry, archery, and light-armed troops against heavy infantry; coerced subjects against free militia; wealthy imperial invaders turned away by pedestrian defenders of farm and family.

The Imperial Persian force was deployed with the center being the crack troops and the flank held by inferior battalions drawn from the conscripts of the Persian Empire. This was exactly as Miltiades had predicted. The Athenians were still at great risk, however, as they only had a little over half the strength of the Persian elite troops. They would also have to advance across an open plain while being fired upon by the Persian archers.

* Philipp August Böckh in 1855 concluded that the battle took place on September 12, 490 BCE in the Julian calendar, and this is the conventionally accepted date. However, the Spartan calendar was one month ahead of that of Athenians, which places the battle on August 12th, 490 BCE.